RURAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY

For

MONGOLIA

CONTENTS

Foreword i

Donor Support for the Development of a

Country-owned Rural Development Strategy ii

Executi ve Summary iii

- Introduction 1

- Principles that Guided the Development of the Rural Development Strategy (RDS) 2

2.1 National ownership 2

2.2 Pro-poor focus, Mongolia’s poverty profile and changes in livelihoods 3

Mongolia’s rural livelihoods 4

2.3 Sustainability 5

2.4 Participation of local bodies and citizens 5

2.5 Implementability 5

2.6 Holistic approach 6

2.7 Timing 6

2.8 Inter-sectoral linkage and co-ordination 6

3. RDS Mission, Development Goal and Objectives 6

3.1 RDS Mission 6

3.2 RDS Development Goals 7

3.3 RDS Objectives 7

4. RDS S tructure, Linkage of Components and Priorities 10

5. RDS Objectives: Challenges and Ways to Overcome Them 11

5.1 Improving Management Capability for Rural Development 11

5.2 Livestock Sector 12

5.2.1 Current challenges 12

5.2.2 Main policy measures undertaken by the government for development of the sector 15

5.2.3 Main direction of donor activities in combating herder poverty 15

5.2.4 Livestock sector development objective 16

5.3 Crop Sector 18

5.3.1 Current challenges 18

5.3.2 Does Mongolia need to have domestic grain production? 20

5.3.3 Crop sector development objective 21

5.4 Agricultural Marketing, Agribusiness and Non-Farm Sector Development 21

5.4.1 Current challenges and opportunities 22

5.4.2 Development objectives 24

5.5 Rural Social Development 24

5.5.1 Current challenges 24

5.5.2 Rural health 25

5.5.3 Rural education 26

5.5.4 Rural social development objectives 27

5.6 Environment Protection 27

5.6.1 Current challenges 27

5.6.2 GOM policies and regulations on the environmental protection 28

5.6.3 Development objectives 29

5.6.4 Forestry 29

5.6.5 Wildlife hunting and fishery 31

5.6.5.1 Wildlife hunting 31

5.6.5.2 Fishery 32

5.7 Rural Infrastructure Development 33

5.7.1 Rural energy 33

5.7.2 Rural communication 33

5.7.3 Rural roads 34

5.7.4 Rural infrastructure development objectives 34

6. Conclusions and Next Steps 35

Appendix 1: RDS outputs and activities targeted to increase incomes and improve the delivery of quality social services for the poor, people from vulnerable

groups and people living in remote areas 36

Appendix 2: Summary of RDS development objectives and outputs 40

RDS Logical Frameworks

Logical framework for building risk management capabilities of herders 42

1. Outputs for building risk management capabilities of herders 43

1.1 Cooperation among herders promoted 43

1.2 Pastureland management 44

1.3 Supply of supplementary fodder improved 45

1.4 Supply of water improved 46

1.5 Veterinary services improved 47

1.6 Capacities for pastoral risk forecasting and response improved 48

Logical framework for intensifying livestock production at optimal level 49

2. Outputs for intensifying livestock production at optimal level 50

2.1 Intensive and semi-intensive livestock pro duction promoted 50

2.2 Mixed livestock and crop farming promoted 52

2.3 Capacity for the quality certification of livestock products enhanced 53

2.4 Research capabilities to improve livestock quality enhanced 54

2.5 Extension capacities to improve livestock production systems and technologies

strengthened 56

Logical framework for ensuring strategic food-flour security 57

3. Outputs for ensuring strategic food-flour security 58

3.1 Risks of losing harvests minimized 58

3.2 Markets for grains improved 60

3.3 Risks associated with wheat and flour imports minimized 61

Logical framework for supporting production and processing of potatoes, vegetables and

fruits 62

4. Outputs for supporting production and processing of potatoes, vegetables and fruits 63

4.1 Access to financial capital to launch production and processing of potatoes, vegetables and fruits provided 63

4.2 Capacities of extension services to advise and train on production and processing of

potatoes, vegetables and fruits enhanced 63

4.3 Support seeds and small –scale irrigation equipment purchasing activities 63

Logical framework for revitalizing the rural marketing system 64

5. Outputs for revitalizing the rural marketing system 65

5.1 Viable institutional structures supported for collection, sorting, primary processing, packaging and the delivery of market information and supplying rural producers with

necessary production inputs and consumer goods 65

5.2 Research capability to improve quality and processing level of agricultural goods for

marketing improved 66

5.3 Delivery of market information improved 67

Logical framework for promoting competitive agro-processing industries 68

6. Outputs for promoting competitive agro-processing industries 69

6.1 Environment conducive to the development of competitive agro-processing SME in rural areas created 69

6.2 Domestic processing industries supported to enhance their capacities to enter the international market

6.3 Rural banking and financial services improved

Logical framework for the development of the non-farm sector

7.Outputs for developing the non -farm sector

7.1 Promoting non-farm SME development based on the utilization of local natural resources, Local materials and skilled rural labour and targeted to meet the local demand

Logical framework for ensuring the delivery of quality social services to rural people

8. Outputs for ensuring the delivery of quality social services to rural people

8.1 Participation of rural communities in planning and implementing investment in social infrastructure increased

8.2 Quality of health services for rural people improved

8.3 Quality of education services for rural people improved

8.4 Quality of social welfare services for rural people improved

8.5 Rural employment support system improved

8.6 Gender equity improved

Logical framework for improving environmental protection sustainable natural resource use

9. Outputs for improving environmental protection, wildlife hunting and fishery

9.1 Capacity of central and local governments to evaluate and monitor the implementation of environment laws improved

9.2 Participation of rural communities in developing and implementing environment laws and regulations increased

9.3 Community-based natural resource management is introduced

9.4 Sustainable use of hunting and fishery resources promoted

Logical framework for improving the forestry sector

10. Outputs for improving recovering capability of forestry resources, conservation and effective use of forestry resources

10.1 Forestry legislative environment and organizational reform enhanced

10.2 Building capability to prevent and fight forest fire, insect pests, and diseases

10.3 Upgrade entomology laboratories

10.4 Effective use of forestry resources and domestic wood production revitalized

10.4.1 Developing forestry resource management plan

10.5 Social Forestry capability in seeds, seedling multiplication, and replanting

Logical Framework for supplying with reliable, sufficient and quality water; protecting and rehabilitating water resources from scarcity and pollution

11. Outputs for supplying reliable, sufficient quality water; protecting and rehabilitating water resources from scarcity and pollution

11.1 Depending on the region, water resources protected and rehabilitated

11.2 Public education campaign on protecting and saving water resources and health, targeted at the different ages and social status of citizens

11.3 Water saving technologies in agriculture introduced

11.4 Water quality improved

11.5 Capability of hydrology improved

Logical framework for rural infrastructure development

12. Outputs for improving rural infrastructure

12.1 Participation of local people in decision making on investment planning and implementation in rural infrastructure increased

12.2 Rural power supply improved

12.3 Rural communication improved through introducing advanced information and communication technology

12.4 Smooth roads that are crucial for rural development ensured by improving the repair and maintenance

12.5 Rural mass media development supported

Foreword

Over the past few years Mongolia has seen adverse changes in the climate. There has been an increased frequency of drought and dzud. Streams are drying up and even major rivers are suffering from lower water levels. All of this has had a devastating impact on agriculture production and the incomes of rural people. It seems highly likely that this weather trend will continue.

Given this new adverse weather pattern it would be very difficult to achieve any development in the rural areas without changes being made in the traditional technologies used in both livestock herding and crop farming.

Although global warming may be blamed for a portion of the climate changes in Mongolia it must be duly acknowledged that human factors have also had a serious impact on the climate. The livelihoods of rural people are declining and rural poverty is increasing because rural people continue to use outdated practices and technology in the changing environment.

There is a much broader context to rural development than simply the food and agriculture, or the farming and herding, issues. Any plan for the rural areas needs to consider well the full range of environmental issues as well as the living and working conditions of all rural residents. Therefore it is essential that the new rural development strategy provide comprehensive guidance to solve all of these accumulated problems.

The Parliament Standing Committee for Environment and Rural Development believes that the preparation and phased implementation of a farsighted, relatively long-term and sustainable rural development strategy is fundamental to resolving many of the problems rural people are facing currently.

Mongolia’s rural development strategy should aim to ensure sustainable growth of the rural economy. Most importantly, however, it should provide an environment in which the well being of every rural person can be assured. This can only be attained by addressing all of the pressing environmental, economic and social issues through a harmonized approach.

The rural development strategy presented here is valuable in that it is comprehensive, based on a holistic approach and includes detailed implementation plans.

This Rural Development Strategy needs to be implemented by incorporating it into the national policy and assuring that government development programs and projects fit within the strategy.

Sh. Gungaadorj

Member of the Parliament

Chairman of the Standing Committee

for Environment and Rural Development

Donor Support for the Development of a Country-Owned Rural Development Strategy

The support has built on work initiated by UNDP, which co-hosted (with the Government of Mongolia) a Government -donor conference on rural development, held in Ulaanbaatar, May 27-28, 2002. Building on this conference, a session of the July 2002 CG meeting focused on rural development. Donors called for further work on the preparation of a long-term strategic plan based on a set of principles that emphasize promotion of local initiative and with the government playing a facilitating role as well as providing important social and other services.

Discussions between the Government of Mongolia, civil society institutions and a donor agency group made up of World Bank, UNDP, FAO and DFID began to identify some of the most needed forms of donor support to assist Mongolia in developing its RDS. Among the conclusions were:

- A sustainable livelihoods approach, building on important previous work, such as the PLSA and inputs to the preparation of the World Bank supported Sustainable Livelihoods Project, offers a powerful analytic framework for synthesizing the elements of the RDS.

- The task of beginning to prioritise possible policy options and operational actions should be done in a series of facilitated, multi-stakeholder forums, involving Government, private sector and civil society institutions.

- The logical framework approach offers a useful tool for facilitating stakeholder discussions.

A one -day planning workshop, involving the full range of stakeholders involved in rural development was held on July 18th 2002. This reached general agreement on the above conclusions on the process to be adopted in preparing the RDS and took major steps in formulating its goals. On this basis, the following donor support was provided:

- A rural strategy support unit that, in addition to providing general facilitation and logistical support, would assemble a resource library of key documents pertaining to rural development in Mongolia .

- Support for a team of local consultants to prepare a synthesis of background papers and to prepare a draft rural development strategy.

- Inputs from an international consultant with extensive relevant experience

- A skilled and experienced facilitator to lead the multi-stakeholder workshop planned for October 2002, following a logical framework approach.

- World Bank staff inputs.

Under the guidance of a Steering Committee formed by the Government, the support team undertook a survey of a representative cross section of stakeholders in four aimags in order to identify the priorities of the rural population. The results were used by the team in discussions with key stakeholders including the PRSP working group, the inter-ministerial committee on rural development, ministries, research institutes, civil society groups and the private sector in order to prepare a first draft RDS for consideration by the October workshop.

During this work and discussions, a number of key themes were developed to provide a holistic context for the proposals and comments of the various stakeholders. A number of significant developments were also highlighted. These are outlined below.

1. Promoting Local Initiatives

Sustainable rural development will only take place if the people directly involved recognise that changes in their thinking and in their activities will bring benefits. Without improvements in the ability of the rural population to express their priorities and of local government to implement changes, the pace of rural development will be slow. This does imply some decentralization of government activities.

One of the main reasons for migration from rural to urban areas is the desire for improved access to a better standard of social services, particularly education and health. Investment is required in order to improve facilities but innovative approaches to service provision are also required to address specific problems such as the relatively high school drop out rate of sons of herding families with limited labour. If the rural people are involved in setting the priorities, they are more likely to provide direct support for service provision.

2. Improvement of Risk Management

Recent experience of disaster in both the livestock and crop sectors has created a recognition that changes in operations and management are urgently needed to mitigate the effects of adverse weather conditions, such as drought and dzud. Projects have provided good evidence that better preparedness through, for example, greater investment in supplementary feed and veterinary care can significantly reduce losses. Such actions are primarily the responsibility of herders, as individuals of groups, but Government has an important role to play in forecasting, in strengthening the disaster response systems and in promoting and testing appropriate insurance schemes.

3. Group Development and Support

Many of the poorest rural households have a relatively small number of animals as their primary source of income. With little to trade, their access to the market is limited, their terms of trade are usually much wor se than those of the richer herders and their ability to obtain inputs such as supplementary hay or fodder is very limited. In order to assist such poor households to overcome these problems, the strategy emphasises support for co-operative action.

Co-operative action is also an essential element in achieving a sustainable usage of natural resources. There is clear evidence of environmental degradation, of which a major element is the degradation of pastures near urban areas as a result of uncontrolled ove r grazing. The promotion of increased community involvement in the management of natural resources is a key part of the strategy.

4. Creation of an Enabling Environment for Rural Economic and Social Development

Even with the emphasis on livelihood improvement for the poorer herding families, there is still expected to be a significant number of families for whom herding is unable to provide an adequate income basis. The strategy therefore emphasises the creation of conditions favourable for the development of other economic opportunities in the rural areas as alternatives to herding and large scale crop production. This requires both an easing of the administrative barriers to enterprise formation and operation, and improved access to finance, particularly micro-credit, which is likely to benefit the poorer sections of the community. Small scale vegetable production, such as is being supported by the “Green Revolution” program is expected to play an important role in improving nutritional standards and in pr oviding income generating opportunities.

The most rapidly growing employment in certain rural areas is unregistered activity in the mining sector. If current trends continue, without regulation, there is the prospect of increasing lawlessness and conflict, environmental damage and of the sub-sector making little or no contribution to Government revenues.

5. Promotion of Agriculture Development and Food Security

Achievement of the PRSP objectives requires economic growth. Part of this is expected to come from an improvement in crop and livestock productivity. Many trials of more intensive cropping and livestock production systems have been undertaken supported by international agencies, but the evaluation has been limited and there are as yet no clearly financially viable models ready for replication and adoption on a significant scale. The strategy therefore emphasises the need for better co-ordination and evaluation of project trials and agency support, a strengthening of the monitoring and evaluation capa bility of MOFA and a preparedness to invest in strengthening the extension service, to provide technical and financial information when successful demonstrations have been developed.

There has been a significant change in MOFA policy, in abandoning wide scale subsidies for wheat farming, and this increases the urgency to support MOFA in developing alternative approaches to facilitating the sustainable development of crop production, within a market economic system.

These foci for the RDS are considered to be fully consistent with the policy of the Government of Mongolia, expressed in the letter to the World Bank of the 25th March 2002 referring to the Sustainable Livelihoods Project. There it is stated that “since July 2000 poverty reduction has been the cornerstone of its Action Plan”: that “policies to promote economic growth should not be separated from those designed to reduce poverty” and that “poverty is not only a matter of insufficient income or levels of consumption; it is also characterized by vulnerability to external shocks such as international commodity prices or natural hazards.”

For the convenience of the various ministries involved in providing inputs to the PRSP, and following suggestions of the Steering Committee, a logical framework system was developed which generally grouped activities related to the responsibilities of particular ministries. Links with other activities and ministries are stressed within the frameworks but these note shows more clearly the holistic approach, which was adopted in preparing the strategy.

In October, (9-11) a three-day workshop was held to review the first draft of the RDS. Participants included over one hundred representatives of all groups of stakeholders including herders and other members of the rural population, local government, ministries and parliamentarians. For two of the days, the logical frameworks were reviewed in detail through a process of facilitated group discussions. During this workshop, general agreement was reached on the broad strategy. A number important clarifications and additions were also made and these have been incorporated in this second draft of the RDS.

Executive Summary

This second draft of the Mongolian Rural Development Strategy (RDS) has been prepared by the Centre for Policy Research. The work was undertaken by a team of Mongolian consultants supported by international staff and under the guidance of a steering committee, chaired by Mr. Gungaadorj. All working documents were written in Mongolian and then translated. This document is designed to provide key inputs for the group preparing the PRSP, which is a cornerstone of Government policy. The initial impetus for this work came from the Government-donor conference on rural development, held in Ulaanbaatar, May 27-28, 2002.

Based on the participative processes outlined in the section on donor support a first draft of the RDS was prepared and discussed in a three day workshop, held on October 9-11, 2002 and attended by over one hundred stakeholder representatives. This second draft incorporates the recommendations of that workshop.

The document uses a logical framework format. The agreed longer -term mission statement for the RDS is to:

Ensure the well being of rural people and their all round development

The agreed Rural Development Goals are:

- Ensuring sustained growth of income for rural people, especially the poor

- Ensuring the delivery of quality social services to rural people

- Ensuring sustainable use of natural resources and the environment

The strategy recognizes that in order to achieve a sustained growth of income the promotion of economic growth is a precondition. However, the policy clearly stated in the PRSP, and adopted in the RDS, is to ensure that all members of the rural population equitably share the benefits of economic growth, principally by providing favorable conditions that would enable people to use their abilities, talents and opportunities to reduce poverty. The pro-poor focus includes measures to enhance the opportunities for people in remote areas to reach markets and to have improved access to health, education and information services. The problems, proposed activities and outputs, most closely related to this pro poor rural development focus, are summarized in Appendix 1.

Key elements of the RDS may be summarised as follows:

Maximum Participation of Local Bodies and Citizens

Successful implementation of the strategy depends upon the overall capacity of governance. According to the Participatory Living Standards Assessment (PLSA), the performance of public administration received poor ratings from the participants because of a lack of administration accountability and effectiveness. The recently approved Public Sector Management and Finance Act and the ongoing Good Governance and Human Security program have a key role to play in addressing the governance issues. The requirement is to overcome the mentality, inherited from the command economy period, of solving problems through top-down directed investment.

The RDS preparation process has confirmed the recommendations of the PLSA, for rural as well as urban Mongolia:

- Give citizens greater voice and influence of patterns of public spending

- Improve the quality and effectiveness of social services and infrastructure

- Invest in public and private actions to reduce risk in pastoral livestock production

In the last recommendation, a key point is that the change in thinking must apply both to the public and private sectors, working in partnership. Effective local participation in setting priorities for the utilisation of Government funds requires increased decentralisation.

Improvement of Risk Management

Discussions during the development of the RDS have shown clearly that the disasters, particularly during the past two years in both the livestock and crop sectors, have focused attention in both the public and private sectors on the urgent need for improved risk management measures. The RDS reflects a widely held belief that climate change will increase the risks for Mongolian agriculture and this ha s stimulated important changes in MOFA policy, such as the abandoning of previous wide scale subsidies for the crop sector.

Pilot programs have demonstrated that greater investment by herders in livestock production, including greater supplementary feeding and veterinary care, can significantly reduce mortality during dzud. There is also an increased recognition that current systems of open access to pastures are leading to over grazing and risks of ecological unsustainability and a lowered ability to cope with adverse weather conditions, such as dzud. For environmental resource management, the strategy therefore proposes as a goal to increase the interest, role and responsibility of local communities in managing natural resources by transferring ownership, custodianship and user rights to local communities.

With the Mongolian climate, such measures cannot eliminate the possibility of catastrophic loss. Restocking programs, supported by international agencies are not a long-term solution and the RDS therefore proposes the development and testing of innovative insurance arrangements to provide a commercially viable safety net. This endorses the approach being pursued under the Sustainable Livelihoods Project. The above measures are largely the responsibility of individuals and groups. Government, however, has a key role to play in disaster mitigation, both through improved forecasting and information provision on disaster conditions and through more effective distribution of emergency relief.

In summary, the objective of building pastoral risk management capability shall be realized through achieving the following outputs:

- Promoting cooperatives and herders' groups

- Sustainable pasture management

- Increasing the use of supplementary fodder

- Improving the supply of water

- Improving the veterinary services

- Improving risk forecasting, response capabilities and disaster management

The PLSA concluded that vulnerability to risk was regarded as the most important dimension of poverty to be addressed. Loss of employme nt, natural hazards (dzud) and the costs of health and education were found to be the most common reasons for families falling into poverty. The RDS proposals in the agriculture log frames address natural hazards. Proposals to stimulate employment generation, with particular emphasis on micro-credit initiatives in the rural areas, are given in the sections relating to agricultural marketing, agribusiness and non-farm sector development.

Group Development and Support

The PLSA found that in rural areas, the poor and very poor made up around half of all households. The primary source of livelihood of many of these families is a relatively small number of animals. With little to trade, such people have limited access to competitive markets, poor terms of trade and limited access to inputs, such as hay and supplementary fodder. The co-operative development, proposed in the RDS, is designed to strengthen the relative position of the poorer herders. Co-operative action is also proposed to promote the sustainable use of natural resources, such as pastures and forest areas. Groups also have a role to play in presenting initiatives to local government and in innovative approaches to social services provision, such as mobile kindergartens.

With donor support, groups have been able to access credit facilities and have started to establish local enterprises to provide non-agricultural employment for group members.

Creation of an Enabling Environment for Rural Economic and Social Development Surveys have shown that one of the main reasons for the recent relatively high level of rural- urban migration is the desire to obtain access to better social services, particularly health and education. With low population densities, the provision of social services is inevitably relatively expensive on a per capita basis. Finance is limited and it is difficult to attract qualified personnel to remote areas. As a result, rural services are often in disrepair, inadequately staffed and unable to provide more than basic services.

Against this background, there appear to be significant differences between sums, which are related more to the effectiveness of the local administration than to the financial provision. For this reason, the RDS lays stress on increased participation of the service users in establishing service priorities and operational support. Any specific proposals for investment or changes in the operational budgets are considered to be beyond the scope of the RDS, at least at this stage.

The agreed rural social development objectives are:

- Increased participation of rural communities in planning and implementing investment to social infrastructure

- Improved quality of health services for rural people

- Improved quality of education services for rural people

- Improved quality of social welfare services for rural people

- Improved rural employment support system

- Improved gender equity

Under the command economic system, large investments were made in the development of the rural infrastructure. Almost all sum centres have electricity, water, heating and telecommunications facilities but there are often severe maintenance and operational problems. Electricity supplies, for example are often unreliable, even in aimag centres, due largely to high fuel costs and difficulties in obtaining payment from consumers. A recent trend is for individual herders to invest in renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power generators but they lack information on the relative advantages of different types of equipment. The lack of a reliable infrastructure inhibits the development of rural enterprises, such as processing agricultural products. Long transport distances from remote areas to Ulaanbaatar, using a very limited road and rail network, inevitably reduce the prices obtained by producers of agricultural products and increase the prices charged for consumer goods.

Even with improvements in the provision of social services, it is likely that there will be a continuing rural-urban migration. With improved agricultural productivity, it is also likely that there will be a decline in the number of people in rural areas relying primarily on crop and livestock production for their livelihoods. An important element of the RDS is therefore the stimulation of non-agricultural activities in the rural areas. In parallel, the development of more competitive markets will improve the terms of trade, and hence the incomes of rural people.

The agreed economic development objectives are:

- Revitalizing the rural marketing system

- Promoting competitive agro-processing industries

- Utilizing fully the potential of non-farm SME development.

During the past ten years, there has been a major programme of legislation and support for the creation of a market oriented economy. The policies on banking, finance, international trade and investment, however, have not yet created a favorable environment for national entrepreneurs. The high real rates of interest, for example, discourage domestic borrowing for investment in fixed and working capital. The RDS proposals for improving the business environment include providing the rural population with improved access to market information, and finance services and support for group formation and operation. Also proposed is a reduction in the significant legal and regulatory barriers to forming and running businesses in rural areas. A recent and rapidly growing source of rural employment is unregistered small-scale mining, particularly of gold. Illegal mining needs to be regularized and regulated to minimize environmental degradation, health risks and conflict.

The RDS team did not have the resources to consider a regional development strategy but concentrated on the process of achieving a consensus among stakeholders concerning the problems and the priorities.

Promotion of Agricultural Development and Food Security

Achievement of the PRSP objectives requires economic growth, in which agriculture and the rural economy are expected to play a significant role.

The RDS proposals for the extensive livestock sector and support for developing small scale vegetable and fruit production are based on the extension of proven actions which will both increase production and benefit directly the poorer sections of the community.

Another thrust of the RDS is the intensification of agriculture production through the development of farming systems, which integrate more closely crop and livestock production. An important element of the intensification plans is an increase in the use of irrigation, both of vegetables and field crops, in order to reduce the risk of total crop failure. Currently, a working group appointed by MOFA is working closely with research institutions in order to develop a new state policy for the crop sector, which moves away from the previously used system of wide scale subsidies on inputs. Preparation of the new policy is expected to include a review of food security considerations. The RDS recommendation is that the food and flour safety objective should be maximum utilization of the cropping industry’s domestic production ability and minimizing the associated import risks.

The current position is that, although many trials of developments such as minimum tillage systems have been undertaken, evaluation has been very limited. Because of the uncertainties, the RDS recomm ends better co-ordination and evaluation of project trials and agency support, a strengthening of the monitoring and evaluation capability of MOFA and preparedness to invest in strengthening the extension service.

For intensification of the livestock sector, the RDS proposals are measures to:

- Improve the Mongolian livestock by using local superior breeds that have adapted to the Mongolian climate and

- Develop sustainable, market competitive intensive and semi-intensive livestock enterprises in areas close to feed/fodder supply and markets.

The RDS Development process

The process of developing the RDS to this stage has proven effective in bringing together many of the ideas present among the various stakeholders and placing them in a clear context of development objectives, using the logical framework approach.

The October workshop, and particularly the working groups, stimulated discussion that led to the creation of a consensus among the stakeholders, with a number of modifications and additions made to the first draft. The participation of stakeholder delegates from different aimags permitted the workshop to highlight the importance of local factors and initiatives in rural development. The introduction of unregistered mining as a topic was particularly informative in highlighting the potential importance of non-agriculture related employment in rural areas.

The RDS is being incorporated into the PRSP but it must be stressed that the RDS development process is not complete. In particular, the output of the working group appointed by MOFA to develop a new state policy for the crop sector will be important both for the RDS and the PRSP since it should provide a basis for planning specific activities and investments as part of the economic development process.

For all concerned ministries, this draft now provides a framework for the review and preparation of investment and operational plans. It should also facilitate the prioritization of proposals, both for ministry programmes and for donor assisted projects.

RURAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY FOR MONGOLIA

1. Introduction

Sustainable rural development is fundamental to accelerating the economic growth of Mongolia, reducing poverty and improving citizens’ livelihoods.

Since the transition to a market economy development strategies have been determined as 4- year action plans by elected governments and development programs and projects along mostly sectoral lines. Although programs and projects supported by international and bilateral donors reflect goals of a strategic nature, they focus mostly on particular issues, and lack coordination and linkages to national development priorities.

Lack of sustainable and long-term development strategies contribute to the unsustainability and discontinuity of government policy priorities, erode the trust of the public and the international donor community in government policies and decreases the effectiveness of resources used. Problem solving is dominated by “extinguishing fires afterwards” and the government efforts often dealw ith symptoms rather than root causes.

The relevance of “The State Primary Rural Policy Directions” issued by the Parliament in 1996 as an effort to determine long-term development strategies has been weakened because both the socio -economic and natural-climatic conditions have changed significantly in recent years. Although more than 20 nation-wide agricultural development programs and projects have been developed, their implementation has been unsatisfactory because of lack of funds, weak specifications for implementation, too much focus on the investments and lack of incentives for ensuring the participation of beneficiaries and building their capacities.

The Rural Development Strategy (RDS) proposes to ensure sustainable rural development by formulating a comparatively long-term and sustainable development strategy and implementing it through mobilising national and international aid resources and through empowering local organizations and individuals to take local initiatives in solving rural proble ms at the local level.

The Government of Mongolia and the UNDP organised a National Conference on Rural Development in May 2002, the result of which was a call for the development of a national rural development strategy through the participation of all stakeholders including ministries working in rural areas as well as the rural residents themselves. With support form the World Band, the preparatory stage began immediately following that conference and involved public polling and surveys carried out in the summer and early autumn of 2002. A Strategic Planning Workshop for Rural Development involving representatives of most stakeholder groups was held in July 2002. This workshop gave direction to the Rural Development Strategy Support Unit operated from the Ministry of Food and Agriculture. The RDS Support Unit comprised of Ms. Jeanne Bartholomew and Ms. B. Nandinchimeg, has played an important role in this process. Based on the mandate of the July workshop and utilizing the information gained from the preparatory work, which included compiling a Rural Development Resource Library the Centre for Policy Research developed a draft RDS in co-operation with the Ministry of Food and Agriculture and other ministries and civil society organisations. The development of the draft RDS was supervised by Mr. Robin Mearns (World Bank) and supported by Mr. Peter McNeill (DFID consultant) and Ms. A. Munkhtuya (World Bank consultant), who compiled, researched interviewed and evaluated information, which served as input for the writing team. The RDS support unit provided translation, editing and input to the writing team. Many national experts outside the government came forward to offer suggestions and provide technical information. In addition, Mr. Derek Poate (DFID consult ant) and Ms. Alice Carloni (FAO) contributed comments and recommendations to improve the draft. Mr. Poate facilitated a national Rural Development Strategy Workshop held in Ulaanbaatar on October 9-11 2002, which discussed the draft RDS and provided many suggestions to strengthen the strategy. The current version of the RDS incorporates the recommendations from the workshop.

Other people, especially Mr. Sh. Gungaadorj, Member of Parliament, Head of the Environment and Rural Development Standing Committee, made valuable contributions to developing the draft RDS. A steering committee composed of Mr. Gungaadorj, MP, (Head of the Steering Committee), Mr. Davaatsedev, MP, Mr. Nergui and Mr. Myahdadag from the Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Mr. Tsedenbal from the Ministry of Finance and Economy, Ms. Erdenechimeg from the Ministry of Social Welfare and Labour, Ms. Erdenechimeg from the Ministry of Health, Mr. Batjargal from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, Mr. Yhanbai from the Ministry of Nature and Environment, Mr. Enkh-Amgalan from the Center for Policy Research (NGO), Ms. Zanaa from the CEDAW Watch National Centre (NGO), Mr. Bat-Ulzii, a herder from the Bayangol sum of Selenge aimag and Mr. Batchuluun, a herder from the Uyanga sum of Uvurhangai aimag provided general guidelines to the Strategy development process after the July workshop. World Bank, FAO, DFID and UNDP provided funding for consultants, consultation meetings, surveys and library development expenses.

The main elements of the draf t RDS are being incorporated into the Government's Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP). Operational and policy aspects of the RDS are also being implemented through the World Bank supported Sustainable Livelihoods Program and other relevant national and internationally supported development efforts.

2. Principles that Guided the Development of the Rural Development Strategy (RDS)

The RDS started with the development of its mission statement. Further a logical framework format was used to specify development goal, objectives, outputs and activities, which are linked to each other through a means - end relationship. The development goal is a general goal that will be achieved when the development objectives are met. In other words, it will be the end result of the work to meet the objectives. Objectives are lower level goals compared to the development goal. They are the positive effects and consequences of the outputs. Output is achieved through implementing a complex set of activities. Activities are very detailed implementation measures to be taken to achieve the outputs. Performance criteria, measurement tools and assumptions are other elements of the log frames. These elements were often missing from traditional ways of developing strategies.

2.1 National ownership

The Government of Mongolia will play a key role in the implementation of RDS together with the private sector, civil society organisations and citizens. Therefore, the RDS was developed by a team of national policy makers, independent researchers and representatives of the civil society. As such the RDS reflects the desires and aspirations of the Government, the civil society and the broader public of Mongolia and is based on their perceptions about the pressing problems encountered in rural development and the solutions to make it sustainable in the long-term.

2.2 Pro-poor focus

A pro-poor focus i.e. increasing income for the rural poor and vulnerable people, enhancing social services for the m and improving their capacities were incorporated wherever possible in the strategy. Enhancing opportunities for people in remote areas to reach markets and accessing health, education and information services was a part of the pro-poor focus. Details of the pro-poor focus are in Appendix 1.

Mongolia’s Poverty Profile and Changes in Livelihoods

The findings of the 1995 and 1998 Living Standard Measurement Surveys (LSMS) suggested that the overall poverty headcount in Mongolia remained more or less unc hanged over this period at around 36%, having risen sharply from a virtual absence of officially recorded poverty until 1990 or so. Changes in the depth and severity of poverty were relatively more significant, suggesting a widening of income differentials between the poor and the poorest. Participatory Living Standard Assessment (PLSA), conducted by the National Statistical Office of Mongolia (NSO), with the support of the World Bank and other international agencies, over the period March-September, 2000, aimed to complement and update LSMS. Using participatory wealth ranking, a method in which differences between well-being categories are based on the participants’ own criteria, changes in perceived levels of well- being were analyzed for the period 1992-2000. New categories of both rich and poor emerged in the early 1990s as a consequence of unequal access to the opportunities offered during the initial process of privatizing many state-owned assets including livestock and urban housing. The gap between rich and poor was perceived to have widened even more markedly over 1995-2000. While some groups were able to take advantage of new economic opportunities, including those with access to information and having ‘connections’ with local officials, many were not. The share of poor and very poor households was judged to have increased over this period at the expense of medium households, as more people fell into poverty than escaped from it.

Rural (and urban) livelihoods in Mongolia have become much more diverse than they were at the start of the 1990s. A wide range of strategies for coping with and adapting to insecurity emerged in the 1990s. The liberalization of fuel prices coupled with the vast distances and low population density of rural Mongolia le d to marked differentials in the prices of consumer goods and the prices paid for producer goods such as livestock products. As a result, geographical location became an important driver of economic opportunity, and migration (both seasonal and permanent) the livelihood strategy of choice for those in a position to take advantage of opportunities in more central regions or larger urban centers. The few rural communities to observe that economic opportunities had improved in the late 1990s were those with access to border trading points with China during a period of high cashmere prices. Family-splitting to take advantage of livelihood opportunities across the rural/urban divide became common. Reliance on inter-household transfers and social networks was vital for the poor, but many (often children) were also forced into degrading or illegal activities such as begging and theft. Illiquidity and crisis in the banking sector meant those salaries, pensions and allowances were often paid late, forcing people to dispose of assets and into a cycle of indebtedness. While support from relatives was crucial for many poorer families, the character of kin -based and other social networks began to shift towards semi-commercial forms and often excluded the most vulnerable. Table Mongolia’s Rural Livelihoods: Summary from Mongolia Participatory Living Standards Assessment 2000 provides with the summary of livelihood profiles in rural areas, main causes of insecurity and vulnerability, and coping and adaptive livelihood strategies in rural areas, sum and aimag centers respectively.

Several conclusions emerged from the priorities voiced by participants in the PLSA that suggest a number of priorities for public policy and action to help create an enabling environment within which people may achieve more secure and sustainable livelihoods. These include:

- A focus on ways of reducing vulnerability, including facilitating access to assets for the poor, and investment in public and private actions to reduce risk in pastoral livestock production

- Improvements in the provision of social services and infrastructure, particularly in rural areas and smaller urban centers, to enhance their effectiveness and increase community involvement

- Promoting access to information and giving greater voice to communities in establishing priorities in patterns of public spending.

Mongolia’s Rural Livelihoods: Summary from Mongolia Participatory Living Standards Assessment 2000

Livelihood Profiles by Well- Being Category (by percentage of household needs met from a particular source) | Insecurity and Vulnerability: Shocks Adversely Affecting Livelihood (in descending rank order by location) | Coping and Adaptive Livelihood Strategies |

Rural Communities (based on a sample of 62 households) Wealthy: Cashmere-56% Wool-11% Agriculture-10% WithMeans: Cashmere-47% Pension and Allowance-11% Meat and Agriculture-11% Poor: Pension and Allowance-49%; Cashmere-20% Salary-14% | Rural Communities (based on a sample of 86 households) - Cost of children’s education

- Natural hazards/loss of employment

- Illness/cost of medical treatment

- Loss of employment

- Theft of livestock and other assets

| Rural Communities Coping Strategies: Inter-household transfers: vertical linkages between wealthier and poorer households, such as labor in return for food/clothing; collective action, including help from relatives Rural-Urban linkages: sending children to urban areas, exchange of goods and services/informal economy, seasonal migration between rural bag and sum centers Livelihood diversification: gathering wild fruits, hunting, growing vegetables Access to credit: formal (banks, micro-credit institutions) and informal (traders, money lenders) access to credit. Formal access to credit is still very rare, and informal lending has very high interest rates (up to 18% a month) Adaptive Strategies: Migration: seasonal (herders move closer to markets, i.e. Ulaanbaatar or other cities) or permanent (rural households move to provincial centers, or to Ulaanbaatar and other large cities) Livelihood Switching: trade, livestock husbandry (“new” herders), wage labor, patron-client relationship Livelihood diversification: otor (long distance movement to good pasture); shift in herd composition in favor of goats for cashmere Inter-household transfers: horizontal linkages between those of similar status, reciprocity between neighbors/friends |

Sum Centers (based on a sample of 28 households) Wealthy: Trade-39%; Micro- Enterprise-39%; Pension and Allowance-14% WithMeans: Salary-21%; Agriculture- 18%; Trade-17% Poor: Pension and Allowance-50%; Micro-Enterprise-21%; Salary-12% | Sum Centers (based on a sample of 36 households) - Loss of employment

- Cost of children’s education

- Illness/cost of medical treatment

- Shortage of cash

- Fuel price increase

| Sum and Aimag Centers Coping Strategies: Reduction of food consumption Inter-household transfers: poor sell goods for the better- off in return for a small fee, wage labor Rural-Urban linkages: family splitting, sending children to Ulaanbaatar or other cities Livelihood diversification: vegetable growing, begging, theft and prostitution Access to credit: more commonplace in sum and aimag centers Adaptive Strategies: Migration: households with means migr ate to cities; vulnerable groups (elderly, single-headed families, poor) remain in sum and aimag centers with few livelihood opportunities Livelihood Switching: establishment of SMEs, trading of goods Mining: households and individuals move to mining sit es for seasonal work Inter-household transfers: horizontal linkages between those of similar status is weaker in sum and aimag centers and cities |

Aimag Centers (based on a sample of 28 households) Wealthy: Trade-60%; Microenterprise- 18%; Salary/Pension-8% With Means: Microenterprise-26%; Pension and Allowance-24%; Salary-22% Poor: Pension and Allowance-46%; Microenterprise-32%; Salary - 16% | Aimag Centers (based on a sample of 33 households) - Loss of employment

- Illness/cost of medical treatment

- Cost of children’s

education - Cost of Tsagaan Sar

and other festivities - Theft of livestock or other assets

|

2.3 Sustainability

Priority was given to ensuring the sustainability of proposed objectives and activities by building the capacities of beneficiaries.

2.4 Participation of local bodies and citizens

The basic principle followed while developing the strategy was to ensure the maximum participation of local government, non-government and private institutions, citizens, herders and farmers in designing and implementing the RDS. This is a way to ensure that implementable targets are selected and implemented through increased interest and contribution of beneficiaries to the implementation process. Only in this way can this strategy overcome the weak implementation of programs and projects of the past, which focused heavily on investments but ignored the desires, and participation of the rural people themselves.

After a series of unfavourable years that caused mass losses of animals and crops both herders and farmers began to recognize that the overwhelming risks can not be overcome in old ways and became more active in searching for new ways to overcome risks and sustain their livelihood. This provides a good basis for enhancing the participatory development processes.

2.5 Implementability

Designing implementable objectives given Mongolia’s natural, climatic, technological and human resources was a key principle in developing the strategy. New and costly production technologies are to be carefully tested, piloted and evaluated for viability in market economy conditions before being introduced.

During the old centralised economic system the process of determining objectives used to focus more on direct implementation methods and did not consider external factors that might influence the implementation. This mentality has not been fully overcome. Rural development is a complex process involving natural, legal, economic, social and political factors. The external factors that directly or indirectly influence the implementation of the RDS were considered under the assumptions in the log-frames.

2.6 Holistic approach

Because of the complex nature of the rural development processes and the failure to achieve desired results to date through non-coordinated sectoral approaches, a holistic approach was proposed to deal with the multitude of challenges faced by rural people. A holistic approach was used as a way in which to address all of the factors that influence the livelihoods of rural people. Holistic does not mean simply “wholly covered” but it means all issues will be brought together on one point, the rural community.

2.7 Timing

The strategy was designed to be implemented over a maximum of 20 years. It is obvious that the implementation period will differ for various outputs and activities. Particularly, the timing will vary based on the implementation priorities, availability of resources and complexity of the objectives.

2.8 Inter-sectoral linkage and co -ordination

In developing the RDS, key sectors such as livestock, crop, agri-business, natural resources and the non-farm sector that have strong interrelationships have been discussed in the most detail. Rural infrastructure and rural social development, which play an important role in rural development but have been developed quite fully and integrated into the National Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper by separate efforts are discussed in the RDS focusing on issues that are seen as crucial to rural development. As such the RDS sections on infrastructure and social services cannot claim to be a complete strategy for those sectors.

The above principles that guided the development the RDS have close interrelationships and mutually reinforce each other. For instance, the principle to ensure local participation facilitates the sustainability and implementability principles. Similarly, the principle of sustainability creates an environment conducive to implementing the pro-poor principle by ensuring the long-term sustainability of outcomes for the poor.

3. RDS Mission, Development Goal and Objectives

3.1 RDS Mission

RDS mission is to ensure the well being of rural people and their all-round development.

The mission stems from the essential needs of rural people to work and live in an environment, which is:

- Provided with equitable opportunities for each to realize his or her talents

- Sustainable

- Protected against any risks and vulnerabilities of a natural, economic or social nature, and

- Capable of keeping a pace with economic and soc ial transformations, globally and nationally

3.2 RDS Development Goals

By developing the Rural Development Strategy the people of Mongolia are seeking to achieve the following goals:

- Ensuring sustained growth of income for rural people, especially the poor

- Ensuring the delivery of quality social services to rural people

- Ensuring sustainable use of natural resources and the environment

Substantial increases in incomes are essential for people to realize their talents and aspirations. For this reason, promotion of economic growth plays a central role in the RDS.

However, growth alone is not a sufficient objective, particularly if it does not involve all segments of the population. For that reason the objective of poverty alleviation has equal standing. Special emphasis will be placed on raising the incomes of the poor more rapidly than for the population as a whole. In other words economic growth will be achieved in a highly equitable manner. Creating an economic environment that will enable the poor to escape poverty through their own exertions and abilities shall be the major principle in alleviating poverty. Dependency mentality, expecting investments from outside the local community such as aid and grants, which causes indolence and feelings of incapability, poses a major stumbling block for the implementation of development policies and programs to alleviate poverty.

The satisfaction of basic social needs is an essential component of the strategy because higher incomes alone do not guarantee suffic ient access to health services, education, pure water and other forms of social infrastructure, including opportunities for cultural development.

The environment not only is critical to our health and wellbeing but more than in most countries, it is an essential source of livelihood for rural people. Shortsighted approaches to managing the environment undercut the basis for the prosperity of future generations and also will damage the health and earning capacity of the present one. Therefore, the strategy gives highest priority to ensuring sustainable use of natural resources.

Maintaining national contribution to food security for the population at a maximum level is a special role of the agriculture sector. In the past 10 years of transition, cropping as well as food processing has substantially decreased. Between 1996 and 2000, Mongolia, a former exporter of food products, became an importer of 17.3 to 46.5 thousand tons of grain, 80.9 to 450 tons of butter and 70% of the total flour consumption, annually. RDS objectives for agricultural production and agro-processing will substantially contribute to improving food security for the population. However, achieving a target of self-sufficiency in all food products is impossible at present. It is recommended that food security be achieved through maximising the domestic potential for agricultural production while taking advantage of international trade.

3.3 RDS Objectives

RDS goals shall be achieved through realizing the following objectives:

- Improving man agement capability for rural development

- Livestock sector development

- Crop sector development

- Rural marketing, agribusiness and non-farm sector development

- Rural social development

- Environmental protection and sustainable use of natural resources

- Rural infrastructure development

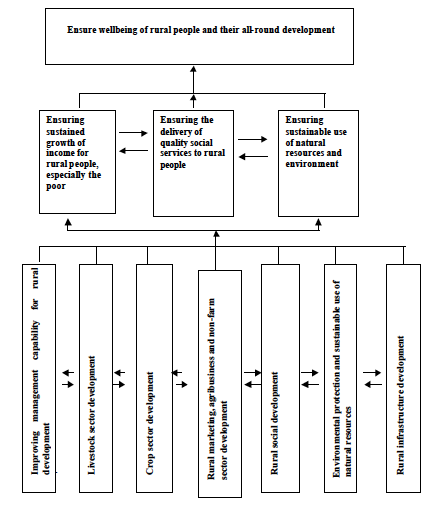

Figure 1: RDS Mission, Development Goals and Objectives

4. RDS Structure, Linkage of Components and Priorities

Vertical linkage between the RDS mission, goals and objectives is shown in Figure 1 . Given the complexity of rural development processes the development goals and objectives are also interrelated horizontally.

At the development goal level, it would be impossible to increase incomes for local people without improving the quality and availability of social services. This is because having good health and education is fundamental to improving the people's livelihood. Likewise, it would be possible to protect human health and ensure the welfare of future generations only if natural resources are used in a sustainable way.

Similarly, the RDS proposes objectives that have strong inter-linkages and are mutually reinforcing. Particularly, livestock and crop sector development objectives are strongly linked through supplying key production inputs to each other - livestock sector with organic fertilisers and the crop sector with feed. Key strategies to diversify the livelihood base thus are linked to reducing vulnerability to future risks. Likewise, the development of rural infrastructure such as energy, roads, telecommunications and information networks is crucial to the development of the livestock, crop and agribusiness industries and the delivery of social services.

Goals and objectives, as mentioned in section 2 of the RDS, are linked vertically through strong cause-effect relationships. For instance, realising livestock sector development objectives such as building risk management capability and intensification; realizing crop sector development objectives such as maximising domestic potentials in wheat production and minimising risks associated with wheat and flour imports; and realizing rural agribusiness and non-farm sector development objectives will substantially contribute to ensuring sustained growth of incomes as one of the development goals.

The development goal of ensuring the delivery of quality social services to rural people shall be achieved through meeting improved rural education, health, social welfare, employment generation and gender improvement objectives.

Given the high concerns about climatic changes, especially, among the top policy makers, the goals of protecting water resources and providing access to water are addressed in a separate logical framework.

Improving rural energy, telecommunications, roads and other transportation networks and information delivery services plays an important role in ensuring the sustained growth of income and ensuring the delivery of social services.

It is impossible to address environmental protection and the sustainable use of natural resources separately from the users or farmers. Unsustainable use of agricultural land causes a major threat to the livelihood of farmers, both in the present and the future. Therefore, the sustainable use of agricultural land is dealt with within the crop and livestock development logical frame works. In addition, issues related to forestry, wildlife and fish that are facing fierce attacks by illegal users endangering rare species to the point of extinction are addressed separately despite their relatively small role in GDP and employment.

RDS objectives shall be achieved through realising related outputs. For instance, the livestock development objective of building risk management capability will be achieved through the accomplishment of the six outputs: promoting herders groups and co-operatives; improving pastureland management; fodder supply; water supply; veterinary services; and risk forecasting and disaster management.

A summary of proposed objectives and related outputs is in Appendix 2.

Prioritisation of development objectives and outputs in terms of their contributions to achieving the development goals and impacts on rural poverty and vulnerability has important implications for sequencing the implementation objectives and short and medium term investment planning. However, detailed prioritisation is a difficult task given the complexity of interrelationships and the different resource endowments of regions. For example, in the Gobi and steppe regions water related objectives rank first while in the more productive forest-steppe regions with a relatively good supply of natural water sources this task will certainly not rank with the same degree.

When ranking comes to particular regions, aimags and sums it should take account of the diversity of conditions.

In Appendix 2 ranking of development objectives is in bold and ranking of related outputs is in normal (non-bold) type. The right hand column ranks priorities. The highest priority is given to number 1.

5. RDS Objectives: Challenges and Ways to Overcome Them

5.1 Improving Management Capability for Rural Development

Whether RDS will be implemented successfully or not depends significantly on the overall capacity of governance , the Government's capability to develop and implement policies.

Especially, overcoming the inherited mentality to solve problems through top-down investment approaches, separating clearly and enforcing adequately the role of state, private sector and others in managing economic development, reducing the role of state, increasing participation of beneficiaries, and making the system of decision-making and implementation more transparent are strongly required. Radical civil service reform is needed to address uncertain prospects for career development and insufficient linkage of merit to promotion. This reform is necessary to prevent pervasive morale decline and corruption among government officials. The recently approved Public Sector Management and Finance Act and the ongoing Good Governance and Human Security program have to play a key role in addressing the governance problems. According to the Participatory Living Standards Assessment (PLSA), performance of public administrations received poor ratings from participants, owing to lack of accountability and effectiveness. Rural citizens had very little contact with aimag and sum governors, and they had very little information on local government activities. Bag governors were rated as being accessible to their communities, but had few decision-making powers. The following recommendations were made from the PLSA on good governance and public policies and actions for rural, as well as urban Mongolia:

- Giving citizens greater voice and influence over patterns of public spending

- Improving the quality and effectiveness of social services and infrastructure

- Investing in public and private actions to reduce risk in pastoral livestock production, in particular, including ways to promote pastoral mobility and community-based pasture land management, in combination with livelihood diversification

The currently low level of fiscal decentralisation inhibits the voice and influence of local communities over public spending programs, while inadequate community participation makes fiscal decentralisation less feasible because local capacity remains under-developed.

Pressing governance issues are not addressed in a separate logical but framework format, however, they have as much as possible been incorporated into proposed ways and processes of implementing the RDS.

In implementing the RDS a high priority is given to ensuring the sustainability of proposed objectives, outputs and activities by building capacities of stakeholders. Institution building is sought to be at the core of capacity building activities along with ensuring access to all types of resources. Providing sustainable use of land and other natural resources through transferring the possession and use rights of the land and other natural resource to the local citizens' formal and informal institutions, co-operatives and herder groups is key to building sustainable use of natural resources and environmental protection. In order to implement this objective complex legal and management measures need to be taken aiming to decentralise the relevant powers and increase local participation.

Ensuring proper coordination of activities across the involved central and local government agencies, private sector, civil society and donors is seen as an important condition for the successful implementation of the RDS. In realizing this condition the Government clearly sees its leadership role and the responsibility for increased participation of other stakeholders and enhanced transparency of the decision-making processes. At the same time the Government understands that the coordination of activities cannot be fully realized without strong initiatives and support from the international and bilateral donors.

The Government's strong willingness to enhance the coordination of activities is based on the strong need to address increasingly common cases in which inadequate coordination results in inefficient use of invaluable efforts and resources.

5.2 Livestock Sector

The extensive livestock industry pla ys a crucial role in the Mongolian economy. As of 2000 the livestock sector makes up one third of the GDP, employment and export earnings.

The major characteristics of the Mongolian extensive livestock industry in the context of the current study are its absolute dependence on an extremely harsh and highly variable natural environment and the resulting basically constant low yield per animal. Mongolian livestock get over 95 percent of their annual fodder from natural pastures, utilising them all year round. Pasture resources are highly dependent on erratic rainfall and their availability is subject to snow cover during cold seasons.

5.2.1 Current challenges

From the late 1950's up until 1990, when Mongolia began the process of economic liberalisation, all members of the rural population were negdel (state co-operative) or state farm employees. During the negdel system the extensive livestock industry moved towards the intensification of production by providing shelter structures and veterinary and breeding services for livestock, making available supplementary fodder and concentrates and irrigating natural pasture.

The intensification process was implemented by a series of large campaigns at tremendous cost. The number of wells and livestock shelters increased from 14.7 and 37.7 thousand in 1965 to 40.3 and 67.5 thousand respectively, in 1985, while the livestock number was held generally constant at around 22.4 m.

Likewise, for the same period, the total harvest of natural hay, the main fodder supplement in Mongolia, increased from 522.2 thousand tons in 1970 to 1275.6 thousand tons in 1985, i.e. 26.7 kg per sheep equivalent. Fodder was mostly produced in the more productive northern regions and a significant portion went to the centrally administered Sate Emergency Fodder Fund (SEFF). The role of the SEFF was to have stocks of hay on hand to be trucked or flown into emergency affected areas to provide short-term relief.

The intensification process undertaken between 1960 and 1990 did not lead to any substantive increase in productivity per animal, i.e. biological productivity. However, it could increase the total output per 100 animals at the beginning of the year, i.e. economic productivity of the industry, through reducing mortality, miscarriages and infertility and increasing the number of animals that produce outputs in any given year. Consequently it can be concluded that reducing mortality, miscarriage and infertility of animals is a more cost-efficient way of increasing productivity for the extensive livestock industry compared with efforts to increase biological productivity per animal. However, this does not mean that any efforts to increase biological productivity are ineffective. There is room for increasing productivity through (i) improving the local Mongolian breeds of animals by using superior local sires with higher yields of cashmere, meat and wool and better resistance to natural hardships; (ii) supporting market-led small-scale intensive and semi-intensive meat and dairy farming in areas closer to big markets or in areas with better conditions for producing feed.

With the beginning of the transition to a market economy in 1990-1993, the livestock population was privatized, and the negdel system, which had been developed over the previo us 30 years, collapsed. As a result, the livestock sector shifted to mainly subsistence- level production based on small household economic units. At that point, it was thought that the privatization of livestock and liberalization of prices for livestock products would promote a smooth shift of the agriculture sector to the market system.

Privatization of the livestock took place before the appropriate livestock support services, capable of functioning under market conditions, and the rural marketing system were established to replace the former negdel service system and the state procurement system.

This passed all of the risks related to weather and prices as well as the responsibilities for production and marketing to herding families who had no experience of running businesses in a market economy. Herders responded rationally to these risks by increasing the herd size to the detriment of free state -owned pasturelands and by decreasing the utilisation of purchased inputs. The number of livestock increased from 25.8 m in 1990 to 32.9 m in 1998. However, because proper breeding methods, veterinary care and selection criterion for slaughter were abandoned the quality of animals deceased and the number animals with weaker resistance to Mongolia’s harsh climate increased.

There was less utilization of supplementary fodder and veterinary services and an apparent unwillingness of herders to use superior stock for breeding purposes, producing the danger of a long-term decline in animal productivity and the quality of output. Hay production declined to 330.3 thousand tons in 1998, i.e. 4.8 kg per sheep equivalent. Most of the pasture wells constructed during the socialist period no longer function. This is because of lack of the ownership or custody rights for the use of the wells. This negatively affects the pasture carrying capacity and reduces the number and range of potential pasture areas. Many livestock shelters were also destroyed due to ‘non-ownership and maintenance’. The fact that the number of experienced herders decreased and the system for replicating the best herding practices through training and retraining of herders was abandoned has greatly contributed to severe losses during natural disasters and eroded the herders' capacity to generate and save incomes in order to overcome the subsistence nature of their businesses.

As a result of constraints that emerged as side effects of the transition period, the main infrastructure and industries collapsed. Due to the lack of available job opportunities many urban residents adopted herding as a main source of income for their livelihoods*. This livelihood strategy increased the herding population and the absolute number of livestock drastically. As of the late 1990s, numbers of herding households doubled and reached 190,000. However, 85 per cent of all herding households currently have less than 200 animals and 63 per cent have less than 100 animals. The capacity of these small households to overcome difficulties related to seasonal movement, haymaking, access to veterinary services, marketing of products, price fluctuations and other man-made and natural risks have substantially weakened. Herders became more vulnerable to poverty. It is estimated that herders need 300 to 400 animals to sustain their livelihood at a satisfactory level. It needs to be stressed that the extensive livestock sector cannot continue to directly support the current number of herding households and that many of the 'newcomers' to herding in the 1990s would rather pursue alternative livelihoods if they had the opportunity to do so.

Under the pressure of increased livestock numbers and the absence of adequate regulations the traditional best-practice grazing patterns have been violated. The subsequent overstocking began to destroy the ecological balance, the keystone of nomadic pastoralism. The overgrazing and degradation of pastures became more serious in areas close to water points and rural settlements. The reserve pastures, which were used in emergencies such as dzud and drought, have been occupied permanently contributing to mass losses of animals during emergencies.

The gap between rich and poor herders has increased and the incidence of poverty among herding communities is becoming more acute. Because of economic constraints for transportation and labor required to make seasonal movements and to market their products, poor herders must stay close to urban centers where pasture quality has declined. This means they are experiencing ever increasing vulnerability to insecurity and risks. There are many young herders and newcomers among the rural poor, and availability of spring and winter camps is extremely limited for them compared to older, established and more financially secure herding households.

Delivery of the appropriate social services is one of the still unsolved problems for herders. Particularly, there is limited access to the achievements of modern civilization. As of 2000, only 10.6 per cent of herding households had electricity sources and 12.8 per cent had te levision sets. Herders are scattered across vast territories, which causes significant logistical problems for the delivery of social services. In addition, because of the constraints caused by the transition to a market economy, budget resources allocate d for rural education and health have been reduced, which negatively affects the rural communities.